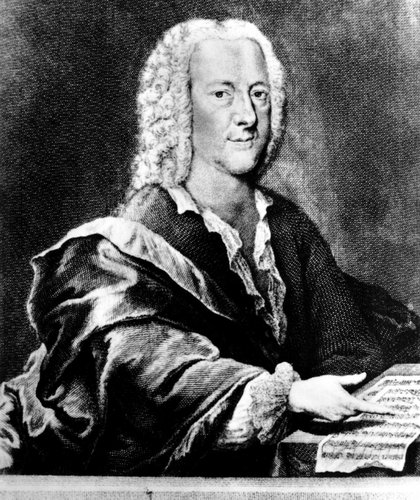

Georg Philipp Telemann

German composer, the son of a clergyman, born at Magdeburg on March 14, 1681, and educated there and at Hildesheim. He received no regular musical training, but by diligently studying the scores of the great masters — he mentions in particular Lully and Campra — made himself master of the science of music. In 1700 he went to the University of Leipzig, and while carrying on his studies in languages and science, became in 1704 organist of the Neukirche, and founded a society among the students, called the “Collegium Musicum.” He wrote various operas for the Leipzig theater before his church appointment. In 1704 Telemann became Capellmeister to a Prince Promnitz at Sorau, in 1708 Concertmeister, and then Capellmeister, at Eisenach, and, still retaining this post, became musikdirector of the church of St. Catherine, had an official post in connection with a society called “Frauenstein” at Frankfurt in 1712, and was also Capellmeister to the Prince of Bayreuth, as well as at the Barfüsserkirche. In 1721 he was appointed cantor of the Johanneum, and musikdirector of the principal church at Hamburg, post which he retained until his death. He made good musical use of repeated tours to Berlin, and other places of musical repute, and his style was permanently affected by a visit of some length to Paris in 1737, when he became strongly imbued with French ideas and taste. He died June 25, 1767. Telemann, like his contemporaries Mattheson and Keiser, is a prominent representative of the Hamburg school in its prime during the first half of the 18th century. In his own day he was placed with Hasse and Graun as a composer of the first rank, but the verdict of posterity has been less than favorable. With all his undoubted ability he originated nothing, but was content to follow the tracks laid down by the old contrapuntal school of organists, whose ideas and forms he adopted without change. His fertility was so marvelous that he could not even reckon up his own compositions; indeed it is doubtful whether he was ever equaled in this respect. He was a highly skilled contrapuntist, and had, as might be expected from his great productiveness, a technical mastery of all the received forms of composition. Handel, who knew him well, said that he could write a motet in eight parts as easily as anyone else could write a letter, and Schumann quotes an expression of his to the effect that “a proper composer should be able to set a placard to music”; but these advantages were neutralized by his lack of any earnest ideal, and by a fatal facility naturally inclined to superficiality. He was over-addicted, even for his own day, to realism; this, though occasionally effective, especially in recitatives, concentrates the attention on mere externals, and is opposed to all depth of expression, and consequently on true art. His shortcomings are more patent in his church works, which are of greater historical importance than his operas and other music. The shallowness of the church music of the latter half of the 18th century is distinctly traceable to Telemann’s influence, although that was the very branch of composition in which he seemed to have everything in his favor — position, authority, and industry. But the mixture of conventional counterpoint with Italian opera air, which constituted his style, was not calculated to conceal the absence of any true and dignified ideal of church music. And yet he composed twelve complete sets of services for the year, forty-four Passions, many oratorios, innumerable cantatas and psalms, thirty-two services for the installation of Hamburg clergy, thirty-three pieces called “Capitäns-musik”, twenty ordinations and anniversary services, twelve funeral and fourteen wedding services — all consisting of many numbers each. Of his grand oratorios serveral are widely known and performed, even after his death, especially a “Passion” to the well-known words of Brockes of Hamburg (1716); another, in three parts and nine scenes, to words selected by himself from the Gospels (his best-known work); “Der Tag des Gerichts”; “Die Tageszeiten” (from Zechariah); and the “Tod Jesù” and the “Auferstehung Christi”, both by Ramler (1730 and 1757). To these must be added forty operas for Hamburg, Eisenach, and Bayreuth, and an enormous mass of vocal and instrumental music of all kinds, including no less than 600 overtures in the French style.