How did a lad from Siófok become an investment banker in London? Why is the winemaking hamlet of Balatonkiliti still the center of his universe? As an international private equity investor, Gábor Illés is at home in multiple countries and industrial sectors, yet his Hungarian roots remain strong. One day sees him building a British biotech company pioneering cancer immunotherapies, the next he is driving the renaissance of the historic iron foundry works of Manfréd Weiss in Budapest’s Csepel district. His story is one of twenty-first-century transformation, a professional life in high finance but a private life that includes two great passions – winemaking and classical music. We hope you enjoy this next instalment in our series of interviews introducing the Board of Trustees behind the Budapest Festival Orchestra.

Lake Balaton was your childhood playground and I feel certain the time spent around the lake has something to do with your interest in winemaking. Where does your story start?

I grew up in Siófok on the southern shore of Central Europe’s largest lake. My grandparents – both paternal and maternal – were not originally from this area, forcefully displaced there in Hungary’s post-World War II turbulence due either to their ‘class’ or their ‘ethnicity’: my dad’s side of the family were land-owning minor nobility, my mother’s were ethnically German. It was thanks to their displacement and the nationalization of their families’ wealth that both of my parents ended up in Siófok as schoolchildren and became classmates in secondary school. For Hungary this was a typical enough twentieth-century story which had elements of loss and tragedy for my grandparents but of rebirth and hope for me and my siblings as we, the new generation, enjoyed an idyllic rural childhood framed by the wonderful lake. I lived in Siófok until the age of 14 and although I have lived since then in many places around the world, my home address in Hungary is still the same: my parents’ house.

Living close to the water’s edge, I imagine you mainly learned to swim in Lake Balaton.

Swimming was everything for me and my two older siblings in those early years. We were keen members of Siófok’s swimming team, with pool training sessions at 6.00 A.M. every morning. Of course, we went swimming in the lake at every opportunity, and each summer we took part in the 5,2km open-water races across Lake Balaton. But the lake offered active kids like us more than just swimming. Often, we went sailing as a family, while my older brother and I were crazy about windsurfing when the weather was stormy. I played ice hockey with my classmates after school in the winter as, back then, the lake would freeze each year making skating very popular.

Life must have been very different in the summertime, with so many foreign holidaymakers attracted to Lake Balaton and its surroundings.

Absolutely. For many years this essentially provided my family’s livelihood. My maternal grandfather, who owned grocery stores in Budapest before they were seized after the communist takeover, vowed never to work for the state. So, he and my grandmother opened a souvenir and tobacco shop in the tourist hub of Siófok. Later, my mother would take it over and develop more of the arts & crafts side. From the age of six, I, too, stood behind the counter, the latest in a family of entrepreneurs! We served our customers mostly in German.

When did you leave Siófok?

I left as a teenager when my sister and I started secondary school in Gyönk, a village in Tolna County about an hour’s drive south from where we lived. Our parents chose the school because it was a German bilingual secondary school that would help us reach full fluency in the language. It was a weekly boarding school, one that fostered a strong sense of community, a feeling of belonging that would play a strong role later in my life, too.

Most of all, it was about broadening our horizons, because the teachers and the students came from so many different places, not only from within Hungary, but also from Germany and Austria. Our education was based on internationalism. We toured Europe with our school’s ethnic German dance group; we published a bilingual student newspaper (called Ein-Stein); and we had the opportunity to attended international student journalists’ annual conferences in Germany, under the banner of “We’re Building Europe”.

These were always great experiences, not to mention the fact that I met my future wife at one of these events when we were both 17. She was there from Miskolc, where she was a student at Ottó Herman Grammar School, specializing in German. Our Hungarian love story began in Germany.

Do you maintain connections with that area’s ethnic German community?

Yes, I’m still in touch with them, and I am a member and supporter of the German Nationality Association in Gyönk. I also feel fortunate because it is in part through language that I’ve been able to embrace so many experiences: I’ve lived in a village, Gyönk, in a small town, Siófok, in a mid-size town, Miskolc, where I started university, in a capital, Budapest, in the Norwegian city of Bergen, where I won a scholarship, and now in London for the past 24 years. It taught me how to communicate with all kinds of people, from financiers to artists, the less well-off to the rich, no matter the setting: village, town, metropolis.

When did you decide what you wanted to be and what you wanted to study?

That was a long process. I remember many lengthy discussions with my father even when it came time to choose which subjects to study at higher level at secondary school! He was a very well-read man with broad horizons.

What did he do for a living?

He graduated with three degrees, but his specialism was as an electrical engineer. Based in Siófok, he served as an executive of the Oil Pipeline Construction Company, which, during socialism, built the entire gas and oil pipeline network of the country. But he also worked in Germany, Kuwait and Kazakhstan, and, after the collapse of socialism, he ran the company’s German subsidiary in Cologne. So, my parents were often travelling or based overseas, something I must have inherited. We continue to explore new places for ourselves, although our lifeline linking us to Hungary remains very much intact.

Did your parents have any specific vision of what professions their children should choose?

They were wonderfully liberal in letting us make up our own minds, but they were keen on giving us the tools to enjoy the widest range of possibilities. They believed it was very important for us all to learn foreign languages, especially English. This was not available as part of the official curriculum back then, so we had private English lessons each Saturday, and we had to take them very seriously. As a result, all three of us had a leg up through English and later would pass advanced-level exams in both German and English. This played a defining role later in our lives. My brother too chose a career in business and my sister qualified as an Egyptologist and also obtained masters’ degrees in German and English. After the birth of her son who is severely autistic her professional career shifted and she became one of Hungary’s leading experts on the treatment of autism, training parents, teachers and educators in the field. She has inspired many, including all of us in the family, to improve how we support all those living with the condition.

To go back to your choice of career, how did you finally decide what you wanted to study?

It was not an easy decision because back then in my teens I was interested in just about everything. I organized a school film club and, as mentioned already, I ran the school’s bilingual student newspaper. At the same time, I was also particularly interested in mathematics, and I participated in several competitions.

I knew I would end up doing something blending mathematics with language and, ultimately, it was my father who suggested I should study economics at university, not least because it kept my options open for the longest time. My mathematics entrance exam turned out very well, but I should really have spent more time studying for the history part! The truth was I was still spending all my free time on the student newspaper, so I became anxious my overall score may not be quite enough for the top university in Budapest. Because my sweetheart (my future wife) was from Miskolc, the obvious thing was to apply to the University of Miskolc as a back-up plan, which is where I was finally accepted.

Ironically enough, she left Miskolc soon after, going first to Germany, and then to the Faculty of Humanities in Budapest. So, I had to “chase” after her, ending up completing my master’s at the Budapest University of Economics (today’s Corvinus University). I also enrolled for an international degree program (CEMS), which awarded me a scholarship to study at the Norwegian School of Economics in Bergen, a coastal city so far away from home I could hardly find it on a map. But this turned out to be another enriching experience not least for the friendships I made there, in particular with a Czech and a German, close friendships that continue to this day.

What field of economics were you interested in at the time?

I chose to specialize in company valuation.

What exactly does this cover?

This covers the nitty gritty of corporate finance: not the day-to-day processes of a company, more the strategic, visionary element where decisions have to be taken about the future – transactions affecting growth, consolidation, transformation, renewal. To be able to predict the future, the valuation of all different scenarios is key and that is the skill I embraced. It moved me instantly into the world not of commercial banking but investment banking, and as I neared the end of my university studies, it became clearer that this was the field I wanted to explore and conquer, ideally in one of the three global financial centers where all major international transactions take place.

How did this become a reality? How did a young man from Siófok become an investment banker in London in the 1990s?

I sent my resume to the world’s leading investment banks, thinking, “Why not aim high? What’s the worst that can happen?”. I soon found out that the worst that could happen was being ignored. I scarcely got any invitations for an interview, apart from one in London, which offered a summer internship. I didn’t go there with any great hope, but I was determined to be as prepared and well-briefed as I could possibly be. Realistically, with Hungary still some way from joining the EU I felt someone applying with my Central European university degree was hardly a top pick. So, I deliberately applied not from Budapest but from Bergen. The internship started just 48 hours after my thesis defence in the summer of 1999. This meant that my wife and I had to miss an event of a lifetime, the total solar eclipse of that summer, which was due to be particularly spectacular at, of all places, Lake Balaton. So, while most of our friends and relatives gathered at our home in Siófok to witness history being made, I was sketching out a financial model in Canary Wharf.

At that point, it was far from certain if any of the thirty summer interns would be offered a permanent position. In the end only four were taken on and I was one of them. I worked in the transportation and logistics group, a great team of professionals with a wide range of international backgrounds who remain good friends to this day. We dealt primarily with airport operators, airlines and logistics companies. I was an investment banker for ten years, moving steadily up the ladder and participating in several very interesting transactions around the world. My most significant Hungarian transaction took place in 2005, when I had the opportunity to manage the privatization of Budapest Ferihegy Airport, my role being to advise the Hungarian State. This is still regarded as Hungary’s largest one-off privatization, with the highest-ever valuation for an airport concession (in terms of EBITDA multiples), a record that still stands. After a decade as an investment banker on the “sell-side”, I accepted the invitation of a former client to become a private equity investment fund manager on the “buy-side”. After another decade or so, I completed the transformation to become myself a private investor.

Do I understand correctly that after a while your focus on airports and airlines evolved into an interest in medical biotechnology?

That is correct. As private investors, we are active in a fairly broad range of industries. One of our early-stage investments, Treos Bio, a pioneer in the development of immunotherapies against cancer, after only a few years was able to raise very significant amounts of capital for its development program. This growth surge made it necessary for the business and financial aspects of the company to be developed and managed too. So, at the request of my fellow investors, six years ago I agreed to take on the role of chief financial and operating officer. Our company is headquartered in London, and today our investors include, among others, the Government of the United Kingdom. We conduct our clinical trials predominantly in the United States, and we have managed to secure significant amounts of U.S. government funding for these. However, most of our research scientists work in Budapest making this very much a twenty-first-century story. Biotechnology, along with pharmaceutical research and development, is a very risky field for investment, and one must be willing to commit for a long time. At the same time, it is this type of risk-taking allied with the talent and drive of scientists that makes the world move forward.

Of course, as an investor, diversification is important both in terms of industrial sectors and geographies, so we have a number of interests in much less risky, “mature” industries. And few are more mature than the latest Hungarian element of our portfolio: one of the country’s oldest industrial icons, the 112-year-old iron foundry at Csepel, where we are working to revive the legacy of Manfréd Weiss, one of the founding fathers of Hungarian industrialization. It’s no small challenge! So, in addition to my private connections, there are also business reasons for me to visit Hungary often.

Many people know that one of the most important activities in your life is winemaking. Where did this come from?

This started about 100 years ago in our family, and we are now in the fourth and fifth generation. My paternal grandparents owned a wine estate at Tab, in Somogy County, not too far from my childhood home on the lake. They also developed two restaurants there, from the 1920s. My grandfather was a winemaker and head waiter, and my grandmother was the head chef and business manager. That was where my father was born.

And then during the communist period they lost it all overnight. They had been put on the “kulak list” – kulak being a term then used pejoratively to identify landowners, employers, bosses, in effect the “enemy of the proletariat”. They had to watch as their flourishing estate and business were divided up and turned almost to nothing. In 1957, they were given back just over one acre, so winemaking remained the family's livelihood. Tiny though this footprint was, their wine became well-known around the region south of Lake Balaton, and several members of the cultural elite at the time, including the actor Ferenc Bessenyei, were their customers each summer.

And then, in the mid-1970s, they both passed away within months of one another. My father stood there with three children and a corporate job with great responsibility. Also, when we were little, he was called up for military service routinely which added to his absences. He didn’t feel he could keep the winemaking going in Tab from a base in Siófok, so, with his older sisters, they sold the estate.

Of course, he later came to regret this tremendously, since it had been a part of his life ever since he was a child. Some consolation came a few years later when as a family we started winemaking again, although not at the original estate in Tab, but on the edge of Siófok itself, in a village named Balatonkiliti so close to the lake we can watch the sunset over the water each evening. We built the vineyard together as a family, doing most of the work ourselves at weekends, on public holidays, whenever the diary allowed. For me, that has become the center of the universe. I was there working yesterday, in fact.

It was unique that you didn’t produce the usual white wines of the Balaton region, but primarily red wine.

That’s right: making red wine doesn’t have the same kind of tradition around Lake Balaton as the white varieties. But my grandfather brought this knowledge with him from Northwestern Hungary, which is where he was originally from. He trained to be a waiter in Vienna before moving to Tab because of my grandmother. The lack of red wine heritage in the Balaton region is surprising because it has all the geological, meteorological and topographical features needed to produce truly world-class red wines – something a number of local wineries have proved since the end of socialism.

In the 1980s, we started entering competitions as a family-owned hobby winery, and the knowledge and skills my father brought with him from home helped us achieve outstanding results from the beginning. My family is very proud of the fact that over the years we’ve managed to win all prizes that a wine can possibly win in Hungary. Whilst our parents lived in Germany in the 1990s, my brother and I, as teenagers and university students, would take care of the necessary winemaking tasks based on our father’s instructions given over the telephone; timing is the most important thing, and you can’t compromise if you want to produce top quality.

Our 1998 Merlot won the grand gold prize in the Competition of Balaton Region Wines. At that point, more and more people were telling us that we must introduce this wine to the general public. In 1999, our parents moved back to Hungary, and things became more serious from that point on. At the age of 55, our father made the romantic decision – with the full support of our mother, I might add – to leave the corporate world behind and become a professional winemaker again. No more hobby winemaking! They bought more land, planted more grapes, built a commercial-sized winery and with that a new chapter was started in the book of our family’s history. Our 2000 vintage was the first one sold in restaurants, under the brand name we had used in previous years’ competitions: “Gyula Illés and Sons.”

Is there any secret to your successes, which you can explain to the average person?

As regards the core of our process, nothing has changed from what our father learned from our grandfather and what we learned from our father. We harvest the grapes when they reach full ripeness (we are always the last to do so in the region), fermentation takes place in old oak vats, we pay great attention to the careful maintenance of the barrels, and we use absolutely no additives apart from sulphur.

There is no one big secret that I could share and help everyone make great wines. The truth is the end result is the sum of a thousand tiny parts – actions, details, reflexes even, some learned, some accidental. Because I didn’t study it from books or in school, I too would need at least ten years to teach someone our winemaking methodology. Over a cycle of 24 months (6 months outdoors, 18 months in the cellar), we perform each step just once. We harvest once, we press the grapes once, etc., and because each year is different, it takes about ten years to encounter all the problems one must learn to manage.

Just like a singer who can’t read music, I also don’t know the exact chemistry of the processes. I don’t think my father and grandfather knew it either, but they learned it from their fathers: this is how we all grew up. I know what to do and when, and I know that I’ve had the most important skill, the fine sense of smelling, ever since I was a child.

You mentioned earlier that life repeated itself – what exactly did you mean?

Just as with our grandparents, our father also passed away very quickly, in his case after a battle against serious illness that only lasted three months. I found myself in the same life-situation with three children, a corporate job with great responsibilities and the question of “now what?”. What in 1975 was the distance between Siófok and Tab was in 2014 the distance between London and Siófok.

I knew how deep the sense of loss was when my father took the decision back then to sell the family winery. I did not want to make the same mistake. So, there was never any chance we would stop winemaking. The funeral took place on a sunny day in March, and I remember going straight to the vineyard from the cemetery. It was time to prune the vines and, as my dad had taught me, timing is everything.

It gave me the greatest sense of encouragement when we managed to win a gold medal in that first year after his death, with a rosé. We missed him deeply, but it was then I realized that winemaking had become a foundational part of me too. The best therapy for the pain I feel over the loss of my father is to be out in the vineyard, making wine and handling the same tools that we used to work with together. In our family, the harvest is the biggest event of the year. We divided up our father’s two main tasks: my brother took over the preparation of the famous harvest stew, while I took over managing the harvest.

Your father would certainly be proud if he knew how successful you have been in carrying on winemaking.

I think he knew that I wouldn’t give up. Quoting swimming icon Éva Székely’s famous book, he always said that “crying is only for the winner.” And there actually have been a few of occasions over the years when we cried tears of joy. Most recently, we brought home two gold medals from the world’s largest international wine competition, the 2022 Berlin Wine Trophy. This year it will be our 40th harvest at the vineyard in Balatonkiliti, and the 9th one conducted by me.

This year, the Budapest Festival Orchestra will also be beginning its 40th Jubilee season…right during the harvest period. How did you grow close to music and the BFO?

Music has been an important part of my life since I was a child. Along with our father’s pipe smoke, we also inhaled classical music at home, although at the time I was of course interested in other genres. I’ve played the guitar since the age of 14; I took up jazz while studying at university, and I’ve also been playing protestant Christian music since I was in my teens. My greatest joy is when our family band gets together in our tiny rehearsal studio in the attic of our London home. I fell in love with classical music again in 2000, when I heard the New York Philharmonic perform Dmitri Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony at the Barbican Centre, conducted by Pierre Boulez. It was a monumental performance, and I still often think back on it. Today, it might be called the Mariupol Symphony. I have listened to it several times since the 24th of February last year.

I first came into direct contact with the BFO about ten years ago through corporate sponsorship. And, accepting the honor of Iván Fischer’s invitation, I’ve been a member of the Board of Trustees of the BFO since 2018, in addition to being a significant private supporter of the orchestra. On the board, I lead the committee overseeing strategy and development. But I enjoy the rehearsals the most! Whenever I can, I attend the orchestra’s rehearsals, because that is where you come to really understand what is going on at the concert in the evening, how it all comes together, how this unique sound is brought to life by Iván and the orchestra. I’ve been fortunate to enjoy some tremendous “rehearsal experiences” with the orchestra in the most outstanding concert halls of Europe and the world.

We maintain a supporters’ circle in the United Kingdom, called British Friends of the Budapest Festival Orchestra (BFO BFO), and we are delighted that the orchestra gives at least one concert each year in London, but more often two or three performances, in fact. The Stravinsky concert most recently at the Royal Festival Hall was just magnificent. In the intermission, we got into such an enthusiastic conversation with our British supporters, our friend the Hungarian Ambassador in London and his colleagues, as well as the BFO management, that this illustrious group of 20 of us missed the bell and couldn’t return to our seats, just before my favorite piece, Petrushka. Ultimately, the organizers were able to let us in quietly, one at a time, to take vacant seats in the last few rows high up on the balcony, which was funny because this very same group of us sat in the “best” seats during the first part of the concert. This allowed us to experience the acoustics from an entirely different place, which in no way made for a poorer experience. It was wonderful. The audience in London, bringing together the broadest cross-section of society, demographics and cultural backgrounds, gave the BFO a standing ovation, the loudest part of which came from the back row of the balcony upstairs! After the concert, the orchestra’s folk music unit improvised a Hungarian folk dance event in the foyer: it was surreal and uplifting to see all these nationalities dancing in unison to Hungarian folk music. And, of course, I have to mention how incredible an experience it was to take part in the presentation of the Gramophone Award. I was and am very proud of the BFO, and I am very much looking forward to the 40th Jubilee season.

Interview by Júlia Váradi.

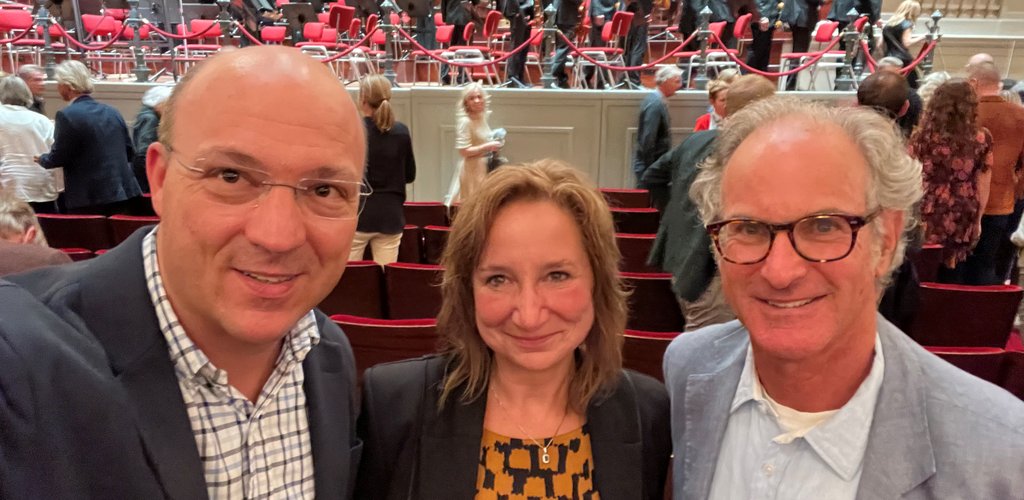

Cover photo shows members of the BFO’s Board of Trustees, Gábor Illés (left), Dr. Andrea Jádi Németh (center) and Alan Gemes (right) at The Royal Concertgebouw Amsterdam after a BFO concert on the 17th of September, 2022.